–What You Don’t Know About Why You Build Models–

Why do we love model railroading so much? Most of us can’t put our finger on exactly why. Sure, we might say we enjoy the craftsmanship or the nostalgia, but there’s something deeper going on—something we feel rather than think about. It’s that gut-level satisfaction when you get a scene just right, or when you instinctively know a locomotive needs weathering even though you can’t explain why. You just know it works. That’s what people mean when they say ‘you don’t know know, but you know’—it’s that feeling of understanding something about the hobby on an instinctive level, even when you can’t put it into words.

So we will explore the “you know” component that may help many others discover the joy of model railroading. But where does one start? It starts by asking the first question that leads us to other thoughtful ideas.

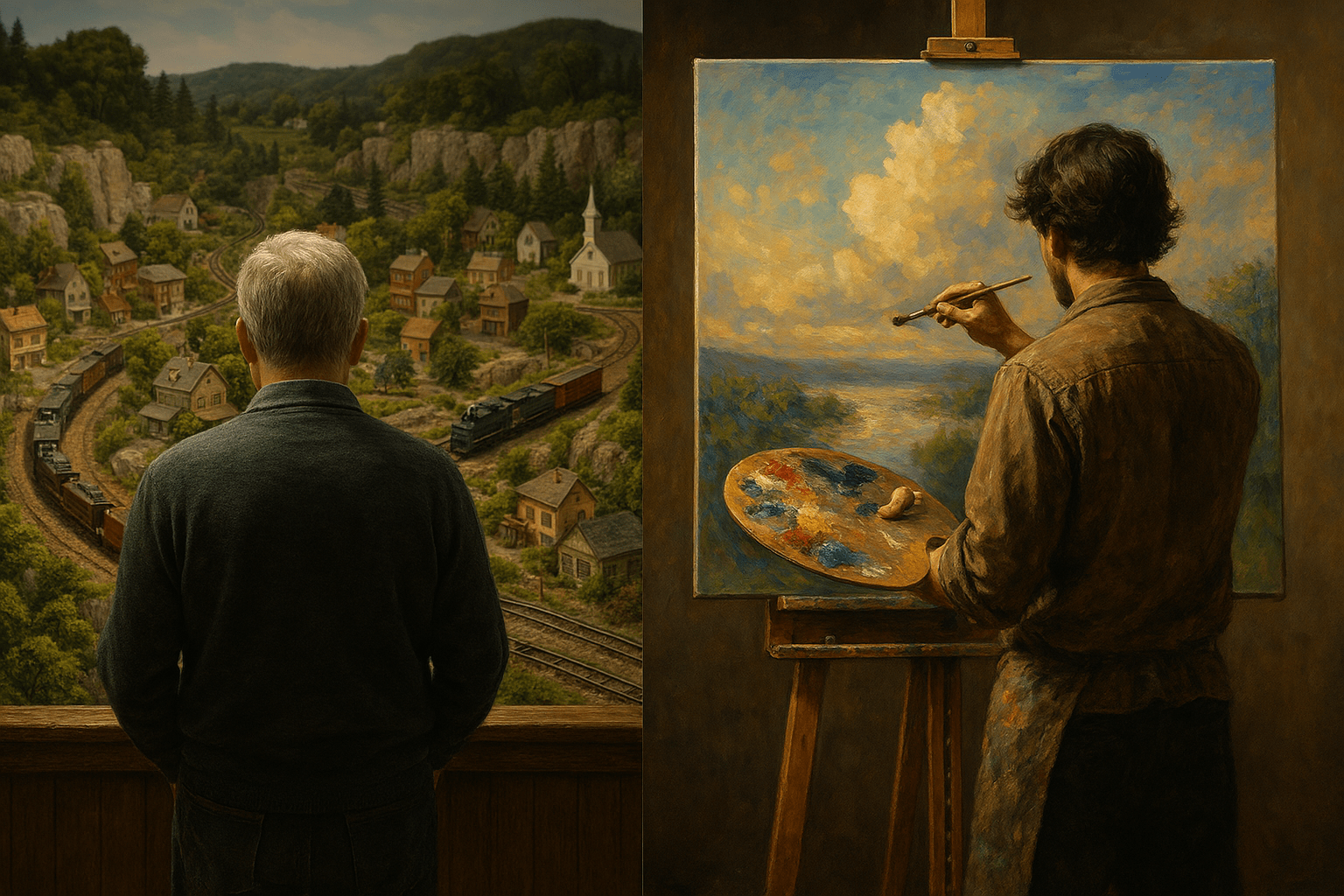

What is it about art and artistry done on canvas and highly detailed mature O Scale model railroad layouts as a canvas that appeals to so many people?

I was lucky to have a college humanities professor who had traveled extensively. She taught us about Greek architecture and art, bringing the textbook to life with slides from her own trips and insights she’d picked up along the way. That class taught me something important: model railroading isn’t just a technical hobby for engineers and science types. Sure, you need some STEM skills, but understanding art, history, and design—the liberal arts—is what really helps you appreciate why this hobby is so satisfying.

It is a fascinating intersection of disciplines. Whether it’s a brush on a linen canvas or a weathered locomotive on an O Scale layout, both mediums tap into a deeply human desire to curate a world. The appeal usually boils down to three core elements: the mastery of scale, the narrative of “the lived-in,” and the ultimate pursuit of a flow state. Curate is a keyword for what we do in the hobby.

1. The Mastery of Scale

In O Scale (1:48), the models are large enough to possess significant heft and “presence,” yet small enough to require surgical precision. And by surgical precision we mean detail often generalized as Proto 48 or fine scale.

The Canvas Effect: Much like a large-scale oil painting, an O Scale layout allows for “micro-artistry.” You aren’t just painting a building; you’re painting the individual rust streaks under a gutter or the texture of a cracked sidewalk.

Depth Perception: Unlike a flat canvas, a model railroad offers a forced perspective in 3D. The artist must understand color theory—using “atmospheric perspective” (lighter, bluer tones in the distance)—just as a landscape painter would to create the illusion of miles of space within a few feet of plywood. The model railroader has the luxury today to mix paints and use various tools to apply color in the development, the micro-artistry that drives an interpretation from the viewer.

2. The Narrative of the “Lived-In”

Mature modeling is rarely about things looking “new.” It’s about weathering, which is where the true artistry lies. I suppose that is why almost every model I scratch build does not look like perfection in a prototype that just came out of the EMD La Grange manufacturing shops. The percentage of time a piece of equipment remains new and shiny is minuscule compared to its life span under real operating conditions.

Storytelling through Decay: A pristine model is a toy; a weathered model is a story. Highly detailed layouts use washes, powders, and airbrushing to simulate the passage of time.

The Human Element: People are drawn to the “ghosts” in the art—the faded Coca-Cola sign on a brick wall or the weeds growing through a rusted siding. It evokes nostalgia and a sense of history that feels tangible. It may evoke a fond memory of having actually being there 40 or 50 years ago in person.

When we are modeling a specific time period, we are striving to make it feel what it was like to be living in that small town or city.

3. Regal Quality “Artistic Sovereignty” and Creative Control

There is a profound psychological satisfaction in being the sole creator of a functioning universe.

Total Environment Design: On a traditional canvas, you control the light. On a model layout, you control the light, the sound, the movement, and the physics.

Sensory Immersion: It’s a multi-sensory “canvas.” The smell of track cleaner, the hum of the transformer, and the tactile nature of the scenery provide an immersive escape that few other hobbies can match. In the most refined layout, it is the scale speed of the train, the realistic control, automation and the sounds of the engines and cars rolling by.

| Comparison | Fine Art | O Scale Modeling |

| Feature | Fine Art (Canvas) | Mature O Scale Modeling |

| Medium | Oil, Acrylic, Watercolor | Mixed Media (Wood, Metal, Resin, Plaster |

| Dimension | 2D (Illusion of 3D) | 3D (Physical Space) |

| Life | Static | Kinetic(Moving trains, Lighting Cycles |

| Perspective | Fixed by the artist | Variable (The viewer moves through the scene) |

The Peer Perspective: It’s easy for outsiders to dismiss model railroading as “playing with trains,” but anyone who has seen a master-level layout knows it’s actually performance art in slow motion. It’s the same impulse that drove the Great Masters—capturing a moment in time and making it immortal.

What are some famous O Scale Layouts that are considered fine art?

In the world of O Scale (1:48), the transition from “toy train set” to “fine art” is defined by a commitment to realism, forced perspective, and historical storytelling. While many famous layouts are in HO scale (like George Sellios’s legendary Franklin & South Manchester), O Scale has several masterpieces that are frequently cited by art critics and hobbyists alike as “fine art.”

Here are a few O Scale layouts that define the pinnacle of the medium:

1. Norm Charbonneau’s “Greenbrook” (The Master of Weathering)

Norm Charbonneau is often considered the “Rembrandt of Weathering” in O Scale. His Greenbrook layout gained legendary status for its hyper-realistic aesthetic.

Why it’s Art: Unlike traditional “hi-rail” layouts that feature shiny locomotives, 100% of Charbonneau’s world was weathered. He treated every locomotive and building like a canvas, using soot, grime, and rust effects to create a moody, industrial atmosphere inspired by the heritage of Pittsburgh.

The Legacy: Though the layout was eventually dismantled, it remains a gold standard for how color theory and texture can turn a model into a gritty, “lived-in” portrait of Depression-era America.

2. Piet van Oorschot’s “Piets Pieck Plein” (Folk Art & Whimsy)

This layout is a unique example of how model railroading can be a direct tribute to a specific artist’s style.

The Inspiration: Based on the drawings and paintings of the famous Dutch artist Anton Pieck, this 1/45 scale (O Scale) layout depicts a fairy-tale-like market square.

The Artistry: Every building was self-built using wood, clay, and paper to replicate Pieck’s nostalgic, slightly distorted, and cozy artistic style. It is widely regarded as a “moving diorama” rather than just a train set.

3. John Sethian’s 2-Rail O Scale Layout

John Sethian is known for proving that O Scale doesn’t need a massive museum-sized basement to be an artistic success.

The Visual Impact: His layout focuses on “composition.” He uses O scale’s physical heft to create “view blocks” and scenes that look like professional landscape photography from every angle. His work often dispels the myth that O scale is just “clunky” by showing surgical-level detail in rural and city scenes.

4. Ray Grosser’s “Soo Line Nostalgia Trip”

Ray Grosser’s work is frequently featured in Great Model Railroads for its ability to capture a specific “vibe”—in this case, the Soo Line in Minnesota.

Artistic Focus: Grosser focuses on the “quiet moments” of railroading. The artistry lies in the flora—the way the weeds interact with the ballast and the specific shade of green in the Minnesota trees—creating a cohesive, painterly environment that feels like a still-life painting brought to life.

5. Jim Richards’ O Scale Mastery

While often overshadowed by the “big names” in HO, Richards is a titan in the O Scale community for his architectural accuracy.

The Detail: His layouts are known for their scratch-built structures that use real materials (scale wood, aged brick). The way he captures the light hitting a factory window or the specific decay of a wooden water tower is often compared to the architectural realism of Andrew Wyeth.

Why these are considered “Fine Art” ?

In these layouts, the “canvas” is no longer the plywood table; it is the atmosphere. These artists use:

Forced Perspective: Painting “haze” on distant buildings to make a 20-foot room look like a 20-mile valley.

Material Integrity: Using real oxides and pigments to create rust rather than just orange paint.

Narrative Intent: Every scene has a “reason” for being there, much like a character in a complex novel or a figure in a Renaissance painting.

Note on Rod Stewart: While Sir Rod Stewart’s world-famous Grand Street & Three Rivers Railroad is often mistaken for O Scale because of its massive size and towering skyscrapers, it is actually HO Scale. However, his layout is the most prominent example of the “George Sellios style” (intense urban clutter and weathering) being recognized by the mainstream art world.

How does John Allen’s Gorre & Daphetid or John Armstrong’s Canandiagua Southern or Bob Hegg’s Crooked Mountain Lines fit into this category of fine art?

These three layouts are the “Old Masters” of the hobby. While John Allen and Bob Hegge primarily worked in HO Scale, their influence on the artistry of the hobby—regardless of scale—is why they are often discussed in the same breath as fine art.

Here is how each fits into the category of “Fine Art”:

1. John Allen: The Gorre & Daphetid (HO Scale)

The Genre: Romantic Surrealism Though it was HO Scale, the “G&D” is the most cited example of a model railroad as a masterwork of composition.

Forced Perspective: Allen was a professional photographer. He used “atmospheric haze” (painting distant mountains lighter and bluer) and smaller-scale buildings in the background to create the illusion of vast, soaring canyons.

The Lived-In World: He was a pioneer of weathering. He didn’t just paint models; he applied “age.” His structures featured sagging roofs and “pigeon evidence” on the eaves—details that elevated the layout from a mechanical toy to a gritty, cinematic portrait of a world “Gory and Defeated.”

2. John Armstrong: The Canandaigua Southern (O Scale)

The Genre: Industrial Realism & Engineering Art Armstrong’s layout is a true O Scale masterpiece. While Allen focused on the “theatre” of the scene, Armstrong focused on the choreography of movement.

The Art of the Plan: Armstrong is known as the “Dean of Track Planning.” He viewed the layout as a puzzle of logistics. His artistry lay in the flow—designing scenes so that a train only passed through once, maintaining the “illusion of a journey.”

Reverse-Engineering Fine Art: He famously “backwards engineered” Edward Hopper’s painting Nighthawks into a 3D O Scale scene. He calculated the exact angles and perspective Hopper used to ensure that when you stood at a specific spot on his layout, the 3D model perfectly matched the 2D masterpiece. This model, replicated Nighthawks is available from David Vaughn through Wit and Wisdom.

3. Bob Hegge: The Crooked Mountain Lines (O Scale / HO)

The Genre: Impressionism & Mood Hegge’s work is the bridge between scale modeling and mood-focused art. He eventually moved into O Scale (specifically Proto:48) because the larger size allowed him to capture the “heft” of the Depression-era Pacific Northwest.

Atmospheric Storytelling: Hegge was a master of “The Vibe.” His layout depicted a struggling, run-down electric interurban line during the Great Depression. The art wasn’t in the shiny engines, but in the texture of decay—the sagging catenary wires, the peeling paint, and the sense of a railroad that was barely hanging on.

I attended the NMRA National Convention in St. Louis in 1970. Bob’s CML layout was open for visitation by attendees. It was the most memorable piece of work that I can ever remember coming away from any convention. I owe it to my Grandfather for taking me because Grand Dad was a traction nut through and through having both worked for the Chicago Surface Lines and modeling traction in O Scale. Perhaps I was very impressionable at that age but I do not think so. It was just a magnificent piece of Art that truly gave me “The Vibe”.

Photography as Art: Like Allen, Hegge used his skills as a professional photographer to frame his layout. His photos in NMRA Bulletin, Model Railroad Craftsman and Model Railroader Magazine were often indistinguishable from real-world historical photography, proving that a layout could serve as a “set” for creating fine-art images.

Comparison of Artistic Styles

| Modeler | Primary Scale | Artistic Contribution | Key Concept |

| John Allen | HO | Verticality & Composition | The “Theatre” of the Layout |

| John Armstrong | O | Perspective & Logistics | “Nighthawks” in 3D |

| Bob Hegg | O | Texture & Historical Mood | The “Gritty” Interurban |

The Peer Perspective: These men didn’t just build “tracks on a table”; they built portals. They treated their layouts like a museum gallery where every angle, shadow, and rusted bolt was a deliberate choice.

We curate our own creations. We live in the ultimate pursuit of a flow state, the deliberate, ongoing effort to live and work in a state of optimal consciousness-often described as being “in the zone” where an individual is completely absorbed, deeply focused, and intrinsically motivated by an activity. That is the model railroader in us. Our audience, like those in the fine art world comes away with impressions, interpretations and opinions. And we all end up learning new things on this journey through the pleasure of creativity.

The Liberal Arts & Science is not just a curriculum, it is a profound shift in perspective. When we say “The Liberal Arts & Science is not just a curriculum,” we are moving away from the idea of a checklist of subjects (math, history, literature) and toward a way of being in the world.

In the context of our discussion on artistry and model railroading, this philosophy fits perfectly. It suggests that true mastery—whether in a physics lab, a painting studio, or an O Scale workshop—is about integration, critical observation, and the synthesis of human experience.

Why it’s more than a curriculum:

- A Habit of Mind: It is the ability to look at a rusted O Scale locomotive and see not just “a toy,” but a study in chemistry (oxidation), history (the decline of the steam era), physics (tractive effort), and art (color theory).

- The Intersection of Disciplines: A “curriculum” keeps subjects in silos. A “Liberal Arts & Science” mindset breaks those walls. John Armstrong didn’t just study engineering; he studied the sociology of how towns grew around tracks.

- The Pursuit of “Why,” not just “How”: A curriculum teaches you how to ballast a track. The Liberal Arts philosophy asks why that specific scene resonates with the human spirit and how it reflects our relationship with time and industry.

The “Artisan-Scholar” Connection

The creators we discussed—Allen, Armstrong, and Hegge—were the embodiment of this idea. They weren’t just “hobbyists”; they were:

- Historians researching 19th-century architecture.

- Engineers solving complex electrical and mechanical problems.

- Artists manipulating light and shadow.

- Philosophers pondering the transience of human effort.

The Insight: When you view a highly detailed layout as a “canvas,” you are actually practicing a Liberal Arts education in 3D. You are synthesizing diverse fields of knowledge to create a cohesive, meaningful whole.

How does this philosophy influence the way you approach your own creative projects? Are you more drawn to the technical “Science” of the build, or the storytelling “Arts” side of the scene?

So now you know, how I know what has kept me plugged into the hobby over the many years with continual pleasure and satisfaction.